There’s an argument to suggest that kinetic sculpture has been around for centuries. Ever since clockmakers introduced mechanised performances to delight audiences on the hour, every hour, there has been a desire to create artwork that moves.

Mechanised sculpture has come a long way since the invention of animated timepieces. But that shouldn’t diminish the brilliance of some of the earliest clockwork sculptures and timepieces, many of which are still beautifully reliable today. Perhaps the best known example here is the Astronomical Clock in Prague that was first installed in 1410.

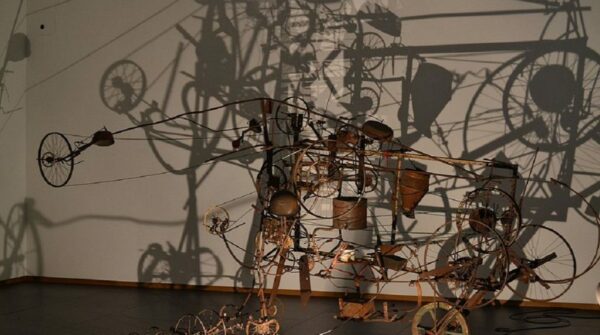

The real coming of age of kinetic sculpture was in the second half of last century. Artists like Jean Tinguely took delight in creating moving artworks that were highly detailed and reminiscent of Heath Robinson sketches.

However, with the advent of microprocessors, previsualisation software and finely controlled motors and winches, designers are now able to introduce a new level of dynamism into their kinetic sculpture.

Individually addressable arrays of nano winches are now commonly used to move hundreds of small suspended objects vertically to create captivating choreography. The mass coordination of a very simple movement combines to deliver hypnotic results. Previsualising the effect in animation software and then sending the motion paths to an automation system make delivering systems like this much less technically demanding than they otherwise might be. The piece entitled Kinetic Rain, from Changi Airport in Singapore shows just how effective these artworks can be.

But there’s more to kinetic sculpture than a relatively dumb array of nano winches. Perhaps the project for which Stage One is best known, the creation of the 2012 Olympic Cauldron was a fine example of kinetic sculpture. Designed by Thomas Heatherwick, this finely controlled artwork moved its 207 stems from horizontal to vertical in a smoothly coordinated and controlled way to mark the opening of the Summer Games in London. To add to the complexity, each of the stems provided a conduit for the delivery of gas to each of the petals, to sustain the life of the Olympic flame.

Other examples of our involvement in kinetic sculpture projects include an artwork installed in the atrium of London hospital. A giant polished sphere takes data from motion sensing cameras and moves around the atrium on a four-way bridle to follow the movement of those inside the building.

There’s an argument too, that some of our ceremony flying projects have delivered elements of kinetic sculpture. Perhaps our first foray into Olympic Opening Ceremonies in Athens in 2004, where we revealed and slowly exploded the Cycladic head, is still one of the best examples of this type of work.

And sixteen years later, we’re still being asked to create artworks and make them move. We have two exciting and challenging kinetic projects currently in development. One is modest in scale and will be an immersive experience that conveys individuals. The other is much larger and will require engineering that will move so slowly that the motion will be almost imperceptible. That’s all we can reveal right now but do keep checking back for updates.

Movement breathes life into artwork. And whilst there’s always some head scratching needed to deliver the repeatable, accurate and smooth motion required, these projects really are some of our absolute favourites to work on.